Phil Murphy is a musician and ethnomusicologist who has spent years studying Andalusian music (Spanish music with Arabic roots), Moroccan music, and music of the Middle East more broadly. This is an excerpt from a conversation we had in February 2024.

C: I was speaking with someone today and they were talking about Pete Seger’s family . . . I didn’t realize his dad was one of the first American ethnomusicologists.

P: Yeah, Charles Seger . . . there are a lot of interesting stories. You may have heard the one about Elizabeth Cotton, the guitar player and her song Freight Train. She was their housekeeper or nanny or something and one day, of course there were instruments all over, she picked up a guitar and was playing it in the dining room. One of the Segers heard her playing and said ‘Oh my God, where did you learn to play guitar like that?’ She said ‘I taught myself’. They recorded her and started promoting her. That’s how she made those records on Folkways or Ash.

C: I didn’t know the whole family was into music so deeply and that they were involved with Smithsonian. I did know Pete Seger had those Smithsonian children’s music records. They were a rich family but were into ‘people’s music’.

P: They were fairly wealthy, it’s interesting, Pete Seger was definitely interested or sympathetic, I don’t know if you could say he was a Communist.

C: Speaking of political difficulties, you had mentioned to me that one of your Arabic professors had some problems because he didn’t want to cooperate with war or intelligence efforts in the middle east.

P: This was one of my professors, he was in religious studies, an amazing guy, he was my Arabic teacher. He was so fluent . . . he’s studied all of these classical Arabic texts and Arabic speakers would say ‘you speak better than me’.

He speaks Danish as well and also French, Spanish, Italian and Japanese. He was studying Turkish and Farsi. He led many lives including living in a village in Egypt to learn these epic poems that are now basically gone. When I was studying with him we worked on translations of biographies of court musicians from The Great Book of Songs. It had not been translated or published before. He’s now publishing new translations of this stuff. There are crazy stories, like a guy who was a court musician who liked to party and he’d get in trouble and have the shit beaten out of him. There’s a story of him hanging out with the kalif’s son drinking wine. He got in deep shit. ‘The kings men took me out and beat me with a sword still in the scabbard until I was red and green and yellow’. Then they threw me in a hole where I was eaten by insects and they left me there for three days. Then they pulled me out and gave me water and told me not to do it again’. But then he keeps getting caught.

C: How did you get into Andalusian/North African/Arabic music?

P: The simple answer is that I got into it through the guitar and getting interested in the origins of the guitar and studying classical guitar. I learned some lute pieces, I learned some of those when I was first studying.

C: All those Spanish composers. Narvaez.

P: Yes, his piece Guardame Las Vacas. ‘Watch the cows’. That’s one of my favorites. After the lute was the vihuela. Through that I got interested in the oud.

C: You got really facile on the oud.

P: I’m looking at it now sitting across from me. My teacher Scott Marcus was a really wonderful teacher of modal theory and improvisation. His specialty is in Arabic music and modal theory. He spent time tracing the history of what would be considered modern Arab music theory. Around the early 1800s to the modern era.

C: Modal theory as in church modes? What do you call them . . .

P: ‘Maqam’ in Arabic is an interesting word that means stations. Describing scale degrees. The treatises get really detailed about the mathematical theory and the tuning aspect. There are also descriptions of how you use the notes . . . they think about them in groups, tetrachords, building the relationships in groups of notes.

C: Similar to Indian music?

P: In some ways it is. If you go back and trace the relationships and the way those cultures interacted in various places and times there is definitely cultural exchange. The same with Persia – the Persian music and the Arab music and Indian music and Turkish music and even the Greek modes that relate to the Western modes. There are certainly relationships between all of those. The thing about raga in Indian music is that it’s different, but it’s not far off in terms of how it works. There is a scale, but the scale has information in it. Maqam is like that too where it has information contained in each tone, it’s much more than a scale.

C: I’m sure you were already familiar with modes in jazz. Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and that stuff . . . but at a certain point you kind of went wild with it. Fast forward a couple of years and you’re playing with orchestras in Morocco.

P: Yeah. I did research before so I was familiar with the differences between Moroccan music and some of the Eastern Arab music, it is quite different. Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine. Those are the main places, when you get to somewhere like Iraq it’s a little bit different. It’s not as well mined by Westerners. Then there’s Persian music, which is distinct.

C: When I was in Morocco and heard the call to prayer coming from the minarets, I’m not sure if ‘music’ is the correct word for that, a lot of people said the calls to prayer sounded quite different there than in Egypt and other parts of the Middle East. Is that related to what you’re talking about?

P: You’re correct in saying it’s not considered music. It does use the same modal stuff as music though. It’s super fascinating to have conversations with people who say it’s not music when you point out it’s using the same mode. They’ll agree ‘it sounds just like that song, but it’s not a song’ because of the function and context of it. They have no problem drawing the line. Of course the call to prayer can sound like music, but it’s not music.

C: I could compare this to some of the Buddhist chants I know. It does appear musical, but it feels like a different activity than making music when you chant them. There seem to be some parallels there. I think some of the melodic patterns are also meant as a memory aid for people who have to memorize long sutras or scriptures. It’s easier if there’s a pattern or it’s hooked onto a melody. That gets into a whole different area of how music recruits a different part of your brain and there’s a lot of crossover there with music therapy.

P: That reminds me of the professor I was talking about who was working on a text called Beni Halal. These texts are incredibly long and one of the things he is interested in is how people memorized these incrediblly long things. Before there were things like television … it was like entertainment, it was very participatory, they remembered it by doing it all the time. It goes back to some of Frances Yates’ [research on memory systems].

C: People memorizing the entire Bible or Koran.

P: In some cultures it’s still common to memorize the entire Koran, it’s definitely a goal. For some people if you’re a good Muslim you do your best to do that.

C: Once you were in Morocco how did you end up participating in some of the rituals?

P: It took a while to build relationships with people so they trusted me. I definitely had experiences where that did not happen. I was living in the old city of Fez. It’s such a labyrinth, it’s really overwhelming. You don’t want to be stuck. It can be daunting. At some point you have to go in there and get lost and figure out how to get out. I knew there were a lot of ‘zawiya’, a Sufi lodge, it translates to ‘corner’. There used to be one corner of a mosque where Sufis would gather. Throughout the city there are all of these zawiya. Some have signs, but some are more hidden. They are often shrines where someone important from that Sufi order is buried. I started finding these places and mapping them out. I started asking around. If there were people there I would introduce myself.

C: Was your Moroccan Arabic good enough?

P: It took me a while. I studied Arabic there before I move there and did a fellowship. I did have a couple of interpreters at first. But then my Arabic got good enough. I got good enough that I could do interviews and record them. It would not have been possible to do the research without the language. If I had known French we would not have had the same conversations. People were so nice once they saw that I had taken the time to learn Arabic.

There was a prominent Andalusian musician who I was working with – his grandfather was a prominent Sufi who had a lodge. He told me where it was and I found it. There was an old guy there who was almost blind who was really welcoming. But there was a young guy who confronted me, saying ‘are you Muslim?’. He said I couldn’t’ come in. There was a rule – actually instituted by the French – that non-Muslims could not enter the mosque. It was a gesture to keep French soldiers out of the space. I didn’t want to lie and say I was Muslim. All I had to do was say ‘there is no God but God and Allah is his messenger’. They told me to just say it and I’d be a Muslim. It would be easy. But I didn’t want to be insincere.

But at another lodge they were wondering who I was and what to do with me. The doorman there was a retired veterinarian. He’d look after the place and sweep it up. He got curious about me. He put me where the women go. It was like a little jail cell where the women go. He told me I could stay there. Every once in a while he’d look up at me and wave. Then once they saw I was really interested they let me sit in a little plastic chair instead of putting me in the women’s room. They were sitting on sheepskin rugs and I was on the little chair. Then eventually the let me sit on the floor.

C: Were you particularly interested in Sufi music or Moroccan music?

P: So going back, I came to it through Spanish classical guitar and lute and oud and then I started learning about Andalusian music which when you think about Spain and the Iberian peninsula and north Africa and gypsies and the reconquests … that was my initial research, that’s where I met they guy I mentioned earlier who’s grandfather had the Sufi lodge, who explained that a lot of the music goes back to Moroccan Sufism. That got me started on it. He pointed out that so much of the Andalusian music is involved with Sufi poetry, but it’s not sacred music but it’s full of Sufi poetry. All roads kept pointing me to Muhammad Bennis. I got to work with him, he’s considered to be a leader of Munshid, not really singer, but it’s kind of similar to the call to prayer we were discussing. He’s in Fez but travels a lot. Anyone interested in Sufi music, his name always comes up. He really took me in and gave me a lot of his time. It took me a while to prove myself, but he understood what I was trying to do.

Last time I was there was 2018. I went to a conference and presented a paper in Essaouira. It was summer and there were some sacred music festivals. One night Muhammad called me up and told me to take a cab, he said give your phone to the cab driver, it was really far away. We finally got out there and he says ‘we’re going to a funeral’. It was quite an experience. It’s three days after the person dies and can go all night. Sufi singers get together and sing poetry that’s really focused on intercession – asking the prophet Mohammed to step in for the deceased on the day of judgement. On the day of judgement the Prophet can argue for your salvation. I didn’t know what was going on till I got there. He liked having me there and having it documented. It was outside under these tents and there’s a huge feast and it just goes till the early hours.

C :What was the ritual itself like?

P: They are dealing with the ‘barzarkh’ or liminal state between this world and the next. The attendants are also using this opportunity to attune themselves to God, to live this life as best they can while thinking about death. The men are engaged in what’s called “the hadra” (literally ‘the presence’). They draw on the sound, words, and bodily movement to annihilate themselves in God. So they are striving toward a state (it’s not necessarily clear who actually reaches this state) in which they temporarily lose themselves (some would say ego) in order to realize that no one and nothing exists except God.

The breath is key. They are synchronizing their breath. They’re inhaling and sounding “Allah” then exhaling and sounding “hayy” (he lives). So God lives, also implying God is eternal. The quality of sound, of singing is also important too. One of my Sufi teachers explained that poems like this are records of elevated states. The poet has recorded his state. When listeners hear these words (especially when sounded by qualified vocalists) they are able to experience these states too.

C: I’m interested in cultural intersections and coming from places of authentic creativity, even when you’re encountering another culture in which you’re an outsider. But I think it can be more of an exchange. For instance, as a young(er) white guy I had some experiences teaching old Black people how to play the blues, which I had originally learned as a kid off of British Invasion records. Or through one of my jobs as a music therapist I became an accompanist for older Haitian women singing combinations of Christian and Voodoo songs. I didn’t know any of the material but was able to pick it up quickly and facilitate a group that wouldn’t have happened otherwise at that place and time and with that group of women. At first glimpse it looks like some form of appropriation but it’s more complicated than that. It was a strange situation, but I think we all got a lot out of those exchanges.

P: There’s a lot written about this in the field of anthropology. People are expected to digest a huge amount of stuff to prepare for doing fieldwork and all of the inherent problems. The power dynamics. Someone like myself is able to get this funding, applying for a grant and going to this place. Like Muhammad Bennis – that was more of an equal exchange. He’s a guy who flies around a lot and performs, but many of the people I worked with didn’t have a lot of money. Many times I was hanging out with or playing with individuals and it was very clear that they couldn’t just get a plane ticket and come to the US.

The same place I was describing before where I got to sit in the women’s section, the guy got really familiar with me and would bring me tea. I would come sometimes and it would just be him and he seemed to like the company. But they would have bigger rituals. I went to one that was a late night gathering. There was one guy who stood out, his clothes were really immaculate and he had on this intense perfume. He was very fragrant. He started eyeing me. He starts talking to me in Arabic and he asks ‘what are you doing here?’ He immediately switches to English when he hears me speak and says ‘what makes you think it’s ok you’re doing this. You’re not Muslim, right?’ I said ‘I’m very interested in Islam and Sufism’. He said ‘don’t you know that studying Sufism before you convert to Islam is like having the key to your own house but choosing to climb up onto the roof and break in?’ Then I never saw him again. With a great quote like that I was thinking ‘this the guy I need to be talking to . . .’

C: He has a point, but also he’s not recording it or documenting it. I was thinking this earlier. If Pete Seger’s dad hadn’t gone around recording people or if Alan Lomax had not gone into prison and recorded Leadbelly the world wouldn’t know that music. I’m sure it was insanely awkward to be in Angola recording prisoners and there’s a whole weird power differential. But also the world has this incredible music that otherwise would have been lost. It’s complicated.

P: There are more and more scholars in ethnomusicology documenting and studying their own traditions. That really makes sense. They’re not running into some of the same issues I did. There are some people very protective who feel like things like Sufism should not be out in the world. In a place like Morocco there are arguments that it should be private because if some people hear it and misunderstand it we could get in a lot of trouble. That’s a common thing in a lot of esoteric traditions. It’s not meant for everybody, One of the most famous Sufi martyrs, Halaj, he was executed because he said ‘I am the truth’. Basically saying that man is God. It has to do with the idea of annihilation, the oneness of God. There is only one God and God is all that there is. If you use the chanting you can have a temporary experience of all that exists is God. So if all is God than I am God. It’s not a good way to keep people in line if everybody is God.

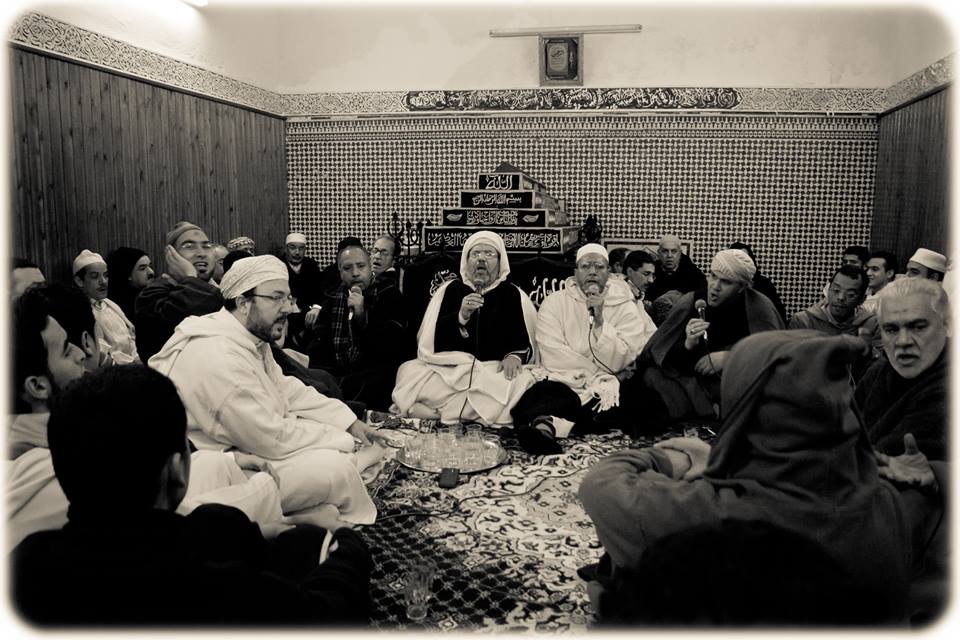

Muhammad Bennis leading a gathering at the zawiya Kettaniyya in Fez (lodge and burial spot of Muhammad al-Kettani, an important Sufi leader). Photo by Phil Murphy.

If you’re unfamiliar, here’s a good selection of classic Moroccan music.